Paris Hilton: Grace through Monetization

In her ghostwritten memoir, Paris Hilton further emblematizes 21st personhood by gushing about fame and business success while blaming her open avarice on childhood trauma

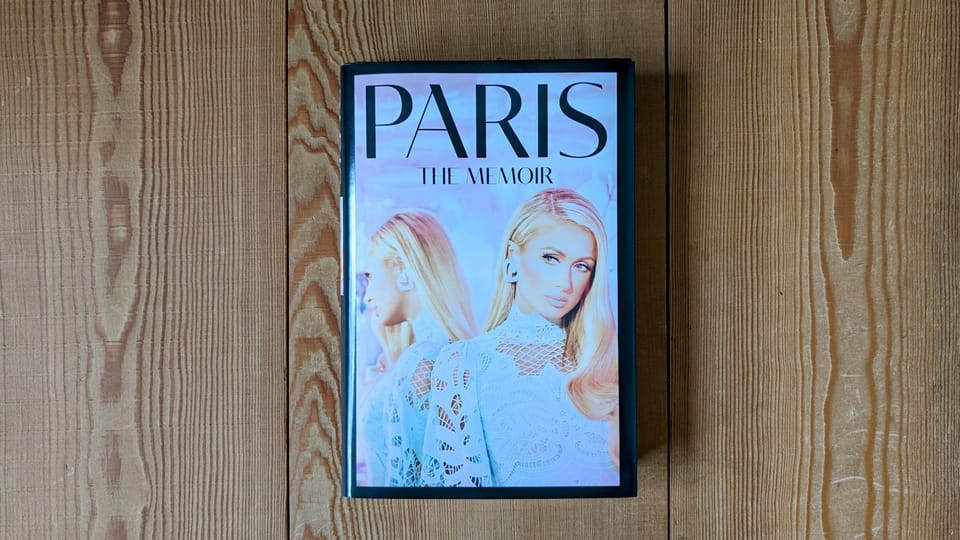

Within a Nineties Alternative worldview, Paris Hilton is an unambiguous societal scourge: a nepo baby, only famous for being famous, who turned her self-created notoriety into a profit center, thus opening a Kardashian-ian rift in space-time that engulfed the entirety of global pop culture. But such a critique sounds very shrill in Our New Century. No one likes a scold, especially when Hilton's flaws and foibles are so obvious that it's trite to list them out. Praising Paris Hilton is the more transgressive move. To Vanity Fair’s Lili Anolik, for example, Hilton is a “21st-century thinker and pioneer reality-TV luminary.” When it comes to reappraisal, however, there is no better sourcebook than Hilton's own recent self-hagiography, Paris: The Memoir.

So how should we understand Paris Hilton? Hilton is, no doubt, one of the most successful individuals of the 21st century, and even beyond her fame and piles of cash, she's now found simpler personal pleasures in pets, marriage, and children. Yet you don't have to be Jordan Peterson to realize that Hilton is most interested in using the book to present herself as a victim. This is apparent on page one, as Joni Rodgers pens the introduction in an intentionally fragmented style to give the reader insight into Hilton's lifelong struggle with ADHD. Then the largest chunk of the book is dedicated to her truly horrible years at abusive reform schools, CEDU and Provo Canyon School. The career-making 1 Night in Paris sextape was yet another source of legitimate psychological damage. Her ex Rick Salomon — poker player and founder of clothing label Hollywood Pimps and Ho’s — sold the video on a website called www.trustfundgirls.com set up by his brother in Czechia.

The trauma is all there to provide critical background for explaining Hilton's divine revelation at age 19, in which she learns that there is only one true god and His name is Mammon. While still a teenager, she tells a family friend, “I want to be famous. I want people to know who I am to be aware of me and I want them to like me so I can sell them things. My product lines. Nicky's product lines. Designers, makers, anything I like. If I say something is beautiful, then they know it must be beautiful. If I go to this club or spa or resort, then everybody wants to go there. I want people to appreciate my opinion as a tastemaker. As an icon. And I want to monetize that, like a lot."

Such an unabashed commercial attitude was a break from the socialite tradition. She was not interested in the beautiful relaxed lives of raw privilege and trust funds. Hilton wanted to immediately spin her genetic golden thread into enviable entrepreneurial profit. Gloria Vanderbilt waited until she was 52 to put her name on designer jeans. At age 19, just two months after 9/11, Paris Hilton wore a dress made from $1 million of poker chips to the opening of the Palms casino.

In throwing herself into self-monetization, Paris Hilton ended up creating the template for 2010s influencer culture: (1) cultivate fame by any means necessary, (2) sell this fame to corporate concerns, and (3) eventually cut out the middleman and peddle mid-quality products directly to fans. Her pathway to extraordinary profit would not require technical innovation, artistic invention, nor financial arbitrage. This then inspired a new class of petit bourgeoisie suburban teens to dream of hawking third-rate private label goods.

Although not mentioned in the book, there was a downside to the Hilton business model: She remained extremely unpopular in her most active years. The Guinness Book of World Records feted her as the most “overexposed” celebrity, and she often made it near the top of the “villain” section of Gallup polls. Yet she eked out a profit in the tender balance between love and hate. In this, Hilton is not the cause of family friend Donald Trump’s political rise, but certainly acted as his harbinger. No matter how many jokes were made at her expense, Hilton's outrageous actions — getting arrested, going to jail, flashing the inner cosmos of her miniskirt — still won the daily news cycle. She then could rely on the most Machiavellian aspects of poptimism to work in her favor: If she made money, she must have done something right — even noble. (Same would go, I guess, for her ex-boyfriend Joe Francis, the auteur behind educational film series, Girls Gone Wild, who is now in self-exile in Mexico).

Providing people with brief momentary entertainment certainly worked as a business strategy, but is it a cultural strategy? For all of the oxygen Hilton sucked out of pop culture in the 21st century, her existence never rose beyond the tier of whoopie cushions, Candy Land, Candy Crush, Dustin Diamond, and Small Wonder. What exactly remains with us as her legacy? There is a recent resurgence of love for her 2006 lite-reggae song “Stars are Blind” — a song she didn't write, which was sued for cribbing from Lord Creator’s “Kingston Town.” Like most reality shows, The Simple Life was not made to be rewatched. Admittedly she may have had some impact on our diets: Hilton’s highly-sexualized slow-motion bikini car-wash advertisement sold a few more Carl's Jr. Spicy BBQ Burgers.

Ultimately Hilton had no interest in leveraging her fame to do something interesting. In reaching Step Three of her business plan, she put her name on a long list of premium mediocre product lines, almost none of which are notable enough to receive specific mention in her own memoir. (Which of the Paris Hilton Fragrances do you wear?) And in the last decade, she has received millions of dollars for competent DJ sets at tourist trap clubs around the world. Hilton, like a retired NFL star who opens a car dealership in his hometown, has transmuted fame into highly lucrative market mediocrity. But hey, it’s a living, and a living that many young people still aspire towards over working in an office.

However much Hilton wants to shape her own narrative, it's clear that her greatest cultural achievement is not culture nor achievement, but being Paris Hilton — someone who seems to have succeeded in "cultural achievement" despite not achieving anything in culture. Her name alone defines the Aughts as an era of pure vanity and vanitas. Yet Hilton frustratingly won't own this fact at all, and on top of the trauma narrative, deploys Nineties ironic detachment as an additional buffer against critique. The Paris Hilton we know is a “character I played — part Lucy, part Marilyn.” You can't criticize Paris Hilton, because we would just be criticizing a character called "Paris Hilton." Or something. Whatever the case, it worked in a graduate student literary theory term paper kind of way. Critics never took her down. She lost momentum after her brief stint in jail (which she claims in the book arose from a single margarita and bad lawyering). But her main career slide came from being flanked by even more notorious, less virtuous rivals of her own creation — et tu, Kimye. And Hilton’s primary medium of reality TV can no longer compete against the power of tiny square and rectangular videos on handheld devices.

So... do we gotta give it to Paris Hilton? Paris Hilton thinks so — out of respect for her as both a victim and a businesswoman. Whether you agree, it's certainly the question of our times. When cultural figures explicitly announce their intention to use culture as a monetization strategy, it's very easy to celebrate their successful monetization as achievement. Paris Hilton set out to make a lot of money at age 19 and she did. No scold can take that away from her. The entire point of the communal value judgements behind criticism, however, is to create a system of incentives and punishments that nudge individuals into making positive social contributions rather than selfish ones. We don't have to scold Paris Hilton for finding money-based palliatives to ease her trauma in our hyper-capitalist, post-moral age — but we should wonder what we got out of it.