Our Geniuses Define Our Times

The superlative adulation for Taylor Swift as an artistic and business genius suggests a shift in the fundamental expectations for cultural excellence in the 21st century

NEW YORK: A launch event with Emily Sundberg of Feed Me, sponsored by Greenlight Books, will be at St. Joseph’s University, New York in Brooklyn on November 18. Please RSVP.

BOSTON: On November 19, I’ll be at Harvard Bookstore in Cambridge, MA. Please RSVP.

During the Popcast emergency pod about Taylor Swift’s new album The Life of a Showgirl, music reporter (and author of the excellent Rap Capital) Joe Coscarelli stated that Swift’s Pixies-interpolating, Charli XCX-punching “Actually Romantic” is “better than anything on Brat put together.” Backlash followed, and on the next pod, Coscarelli clarified the reasoning behind his critical judgement: What he wants “out of a popstar and a pop song” is “fastball down the middle, big, dumb, catchy hooks.”

“Fastball down the middle” is a pretty good metaphor for a Taylor Swift song. The fastball is the most common pitch, which goes exactly where the batter thinks it will go. Much like a fastball, Swift’s music is a driving, high-energy version of a classic pop song, which she achieves through the deployment of the exact chord progressions and melodies that her audience expects.

Now to extend the metaphor, the opposite of a Taylor Swift song would be a curveball, which at first appears to be normal but suddenly swerves in another direction. Where fastball songs deliver to expectations, curveballs surprise.

As forced as this sports metaphor feels, it conforms well to the foundational ideas of early 20th century art criticism. Russian Formalist Viktor Shklovsky built his theory of art around the idea of ostranie — artworks that “defamiliarize” the familiar. In his book The Prison-House of Language, Frederic Jameson explains that ostranie-based art is “a way of restoring conscious experience, of breaking through deadening and mechanical habits of conduct.” And even when art fails to achieve full mind-shifts, its strangeness can at least be a source of new stimuli. Avant-garde artists in the 20th century believed art should always be a curveball; a fastball is not art.

Shklovsky’s theories are, of course, built on top of an even more influential theory of art: the 18th century philosopher Immanuel Kant’s definition of what makes an artist a “genius.” He laid out three criteria for attaining genius status: (1) the creation of fiercely original works (2) which over time become imitated as exemplars, and (3) are created through mysterious and seemingly inimitable methods.

Meanwhile in 2025, Taylor Swift — the proud thrower of fastballs, not curveballs — has been anointed a great “genius” of our times. Harvard Business Review editor Kevin Evers recently published There's Nothing Like This: The Strategic Genius of Taylor Swift about Swift’s acumen as a businessperson. And then Harvard professor Stephanie Burt just released Taylor's Version: The Poetic and Musical Genius of Taylor Swift. Like Jay Z, Swift has achieved genius in both fields of business and art.

What qualifies Swift as a genius? The business part is self-explanatory: She’s accumulated more than a billion dollars from her music career. But what makes her a Wordsworth-level poetic genius? In Publisher’s Weekly summary of Burt’s book, “the secret to Swift’s success” is “her ability to speak directly to women, and to keep aspirational and relatable qualities in tension.”

In this, Swift offers us something new: She's an anti-Kantian genius. Her work is always “direct” and “relatable” — no curveballs, no ostranie. Her constant deployment of existing conventions is not an artistic failure, but a brilliant artistic statement of audience expectation management. Burt lauds Swift for her “deep attachment to the verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge conventions of modern songwriting.” This is true: Swift is quite dedicated to specific patterns from recent hits. Many, many musical artists have used the I V vi IV chord progression: Better than Ezra’s “Good,” Justin Bieber’s “Baby,” and Rebecca Black’s “Friday.” Maybe some of these artists even wrote one additional song repeating the same chord pattern. Swift, in her dedication, has actively chosen to deploy the same recognizable chord sequence 21 times. (And she’s used the alternatively famous IV I V vi and vi IV I V progressions at least 9 times each.)

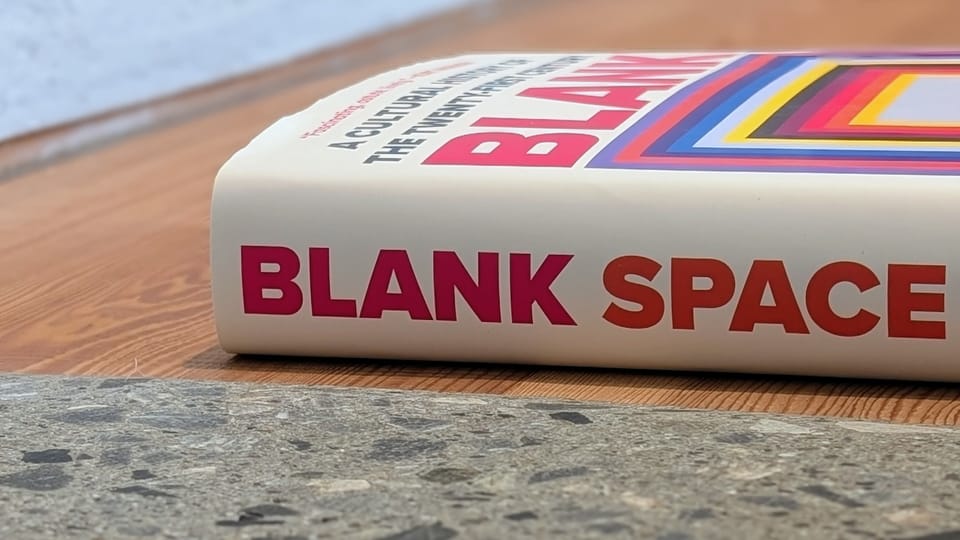

Swift's artistic strategy also involves creating songs that sound like songs that everyone already likes — a rejection of the Kantian idea of being the first to create a formal innovation that others copy. Jaime Brooks pointed out that her mega-smashes on 1984 were clear soundalikes: She ordered Max Martin and Shellback to create a copy of Pharrell’s “Happy” and got “Shake it Off,” and asked for a Lorde “Royals” and got “Blank Space.” And to round things out, her process is not particularly mysterious. When she decided to sound like Max Martin to reach a broader audience, she hired Max Martin.

Swift's genius status also demonstrates how little tension remains between art and business. In my new book Blank Space, I discuss the rise of what I call entrepreneurial heroism: “the glorification of business savvy as equivalent to artistic genius.” Avant-garde artists never made billions, because ostranie is a bad strategy for securing extraordinary profit or maximizing shareholder value. But when genius is simply “clever deployment of the thing everyone already wants,” there is no longer an inherent conflict with business logic.

So we can conclude that "genius" in 2025 is no longer Kantian. Many may celebrate this as greater egalitarianism, and my annoying use of the word "Kantian" very likely bolsters their case. This outcome also may be an inevitable outcome of the avant-garde's success. As Jameson writes, “For generations which have been raised on modernistic and stylized art and decoration and for whom such stylization needs no defense and seems utterly natural, an inner tension and dynamism seems to have gone out of the polemic.” This describes our times very well. There's no more urgency in uplifting Kantian geniuses when we're born into a world permanently brightened by their innovations.

But the designation of certain people as geniuses has long-term consequences. The artistic exemplars set the horizon for future behavior across the entire cultural ecosystem. In 1937, the painter and theorist John D. Graham wrote, “Without genius” — and he means Kantian genius — “all the cultural activities of humanity would soon degenerate into clichés.” Well, where are we when our “geniuses” achieve their superlative status through the active embrace of cliché?