On Writing a History of the 21st Century

My new book, Blank Space, is a cultural history of the last 25 years, scheduled for publication in November 2025. Now that I've finally emerged from writing and editing, here are some early thoughts about the process.

I know: I haven't been sending very many newsletters.

This is because I spent 2024 in an insane sprint to write a cultural history of the 21st century — in less than a year. On January 6, I turned in 110,000 words, which we've thankfully slimmed down, but the endnotes are still 45,000 words, because I referenced a lot of material. (The index is likely to be very long, as it includes everything from BAPE to BAP, Jessica Simpson to Ashlee Simpson, and Kanye to Ye.) The title of the book is Blank Space, and it’s scheduled for November 2025.

On writing a cultural history of now

In not writing the newsletter much, I have many pent up ideas I’d like to explore in future essays. But before I start on that, I thought it would be good to reflect on what it’s like to write an “ultra-contemporary” cultural history.

After the quite theory-heavy Status and Culture, I wanted to write another linear history like Ametora. The resulting book is a quasi-hybrid of the two — analytical history applied to extremely non-obscure subject matter. Is this my most “accessible” work? Lord knows I tried. In the few rare times I bring up critical theory, it’s mostly to show how Adorno, Jameson, and co. predicted everything that happened. But don’t worry, those eggheads are balanced out with appearances from beloved celebrities like Rick Salomon, Amber Rose, and Dov Charney. (But not Chet Hanks: “White Boy Summer” got cut out of the book just like real life).

Some thoughts on the writing process:

1. Writing about the present means you’re never off the clock

When researching 20th century European art, very little in the news cycle affects your work: Picasso is dead. By contrast, writing about present times means that every single morning begins with encountering at least four news stories and essays to consider for inclusion. And the news cycle forced me to continually update the text.

For example, the Hawk Tuah Girl:

• “There’s a new thing on the internet — the Hawk Tuah Girl.” → I write a few sentences on Haliey Welch (and get really good at spelling it "Haliey")

• “Oh, the Hawk Tuah Girl went to a crypto conference.” → The sentences become a short paragraph

• “The Hawk Tuah Girl now has the #3 podcast in America.” → The paragraph becomes a section-opener

• “The Hawk Tuah Girl launched a memecoin.” → Haliey Welch now embodies the economic aspirations of her entire generation

• “The memecoin was a rugpull, and she’s in hiding.” → More furious edits, uplifting Welch to the greatest possible embodiment of culture in our times (after DJ D-Sol)

• “The Hawk Tuah Girl disappeared and maybe wasn’t anything at all.” → Anxiety, doubt, fear

This is all to say: it’s very hard writing an ultra-contemporary book, and I generally would not recommend doing it. My meager attempt has made me even more grateful for our incredible slate of contemporary writers like Ryan Broderick (Garbage Day), Kaitlyn Tiffany, Kyle Chayka, Casey Lewis, Max Read, Katherine Dee, and Kelsey Weekman (among many, many others) for covering internet culture and its impact on everything else. Garbage Day in particular has been fascinating to follow over the last few years; Broderick’s reporting on net-right, bro-culture went from writing about “here’s Adam22 and some other weirdos lol” to becoming a must-read outlet for understanding America's political collapse.

- To structure the book, you have to know the ending

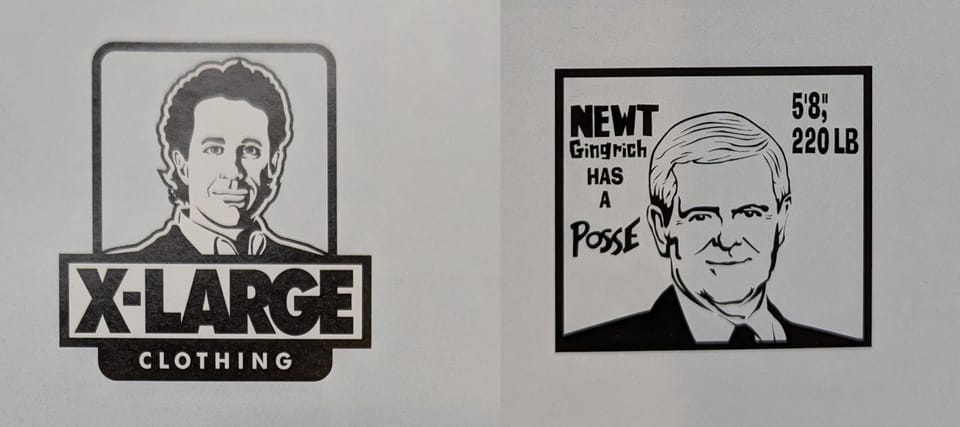

Not to put the entire arc of global cultural history on U.S. presidential politics, but the 2024 election asked the question, was Trump’s first term an outlier or does it represent a durable shift in values? I had to write most of the book not knowing how the American electorate would answer this question, but once Trump won, it streamlined the entire narrative. The history now points to the rise of a very clear ideological stream I call the "counter-counterculture" — the reinvention of "cool" transgression as anti-liberalism that began with Gavin McInnes’ years at VICE and appeared later in 4chan trolling and helped the alt-right go mainstream. In combination with canceled celebrities, the manosphere, and the Zynternet, anti-liberalism has powered the most popular "alternative" culture of our era, and American voters and institutions have now handed this coalition the reins to government with no guardrails.

3. You feel the anger of readers while you write it

Not to glorify my generalized anxiety as a craft secret, but I have talked in the past about writing with a "devil on my shoulder" who constantly warns me that I'm getting things wrong. When I was working on Ametora, I was convinced that a gang of denim snobs would be looking to jail me for missing some minor details. (Don't tell them I remain skeptical of Edwin's claims to using selvedge denim from South America in the 1960s!) But at least the fear of the bad-faith reader-mob imbued me with a vigilance to try and get things right.

The nice thing about Ametora, however, was that it's an extremely obscure history. This time I'm writing about a period every single person lived through and has strong opinions on. Moreover, half the fun of reading a cultural history is waiting for your favorite artworks and moments to show up in the story.

But there is no way an author can include everything. Like all of my writing, this new book includes an unhealthy number of proper nouns (there's a reason I do this that I'll explain some time). Ultimately, however, the book is about the changes to our collective values over the last 25 years. And under that framing, many important and popular things got cut for space or because they felt repetitive to other examples. And with every cut, I got to feel the future vitriol of readers in my head: Where is “Peanut Butter Jelly Time”? Why no discussion about In Rainbows’ “pay what you want” pricing model? Why no trenchant analysis of Vanderpump Rules?

On the bright side, writing this book made me excited to read other cultural histories of the period that focused on particular areas and fields. Just off the top of my head, here are some free ideas for books that should exist (with titles):

(1) PWNED: A deep cultural history of gaming in the 21st century

(2) PLATED: A cultural history of food in the social media age

(3) CREATIVEMAXXING: A passionate defense of 21st century creator culture

On having written a cultural history of the 21st century

I keep semi-joking that writing a cultural history of the 21st century “radicalized” me, but I certainly reached the end of 2024 feeling that the current media environment is not very healthy for the human brain. There is way too much information to process. I couldn't possibly be the only person who feels this way.

A good illustration of this is Ben Dietz's incredibly good newsletter [sic] that rounds up the best cultural reporting/criticism of the week. There are so many links in each issue, because there is so much good cultural criticism right now. Every issue is both enlightening and makes me feel total despair because I can't get through it all.

So in finishing the book, I promised myself that I would adjust my media consumption habits and give myself more quiet during the day. But this means I’m listening to way fewer podcasts and reading fewer newsletters. There are surely people out there excited about reading multiple 5,000+-word missives in their daily inbox, but I personally struggle to get through them all. (Today's newsletter is 1,505 words BTW.)

Before I started writing Status and Culture, I spent four or five years methodically reading through about 40-50 books a year that I considered the authoritative works on cultural and social theory. And this left me with a long-term conviction that there’s so much depth and forgotten wisdom hidden inside older books. I have ridiculous number of those old books in my house staring at me, and I'm excited to dive in. But there is a trade-off: reading old books means not consuming contemporary forms of media.

I did a year of 24-7/always-on-the-clock attention to contemporary culture, but I would like to try something else for a while. I need a break. I realized this when I started fantasizing about being a nomadic herder on the steppes who could know all of this terminally online information if he wanted but whose life doesn't depend on it.