Notes on The Nineties

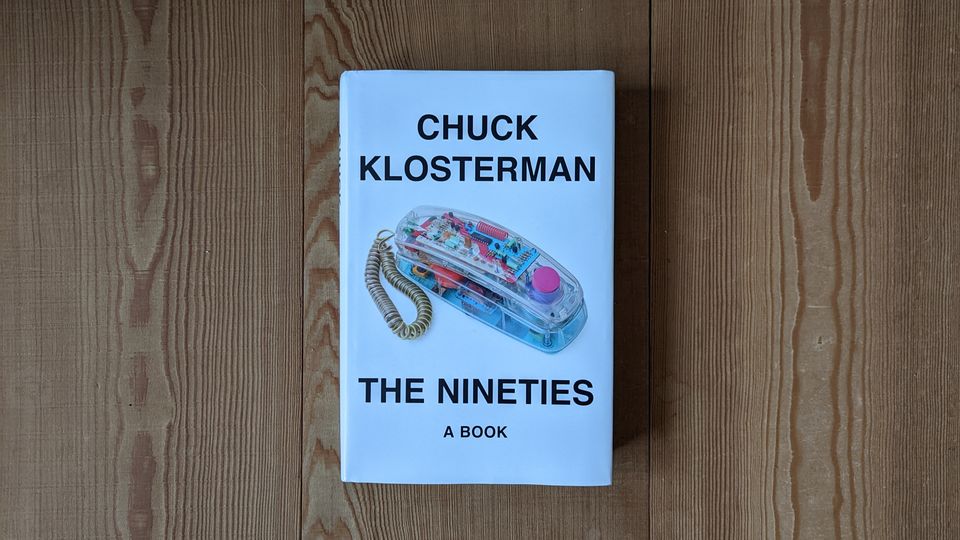

Thoughts on Chuck Klosterman's The Nineties: A Book and the lived experience of the Nineties, a particular decade

I. Remembering the Triumphalism

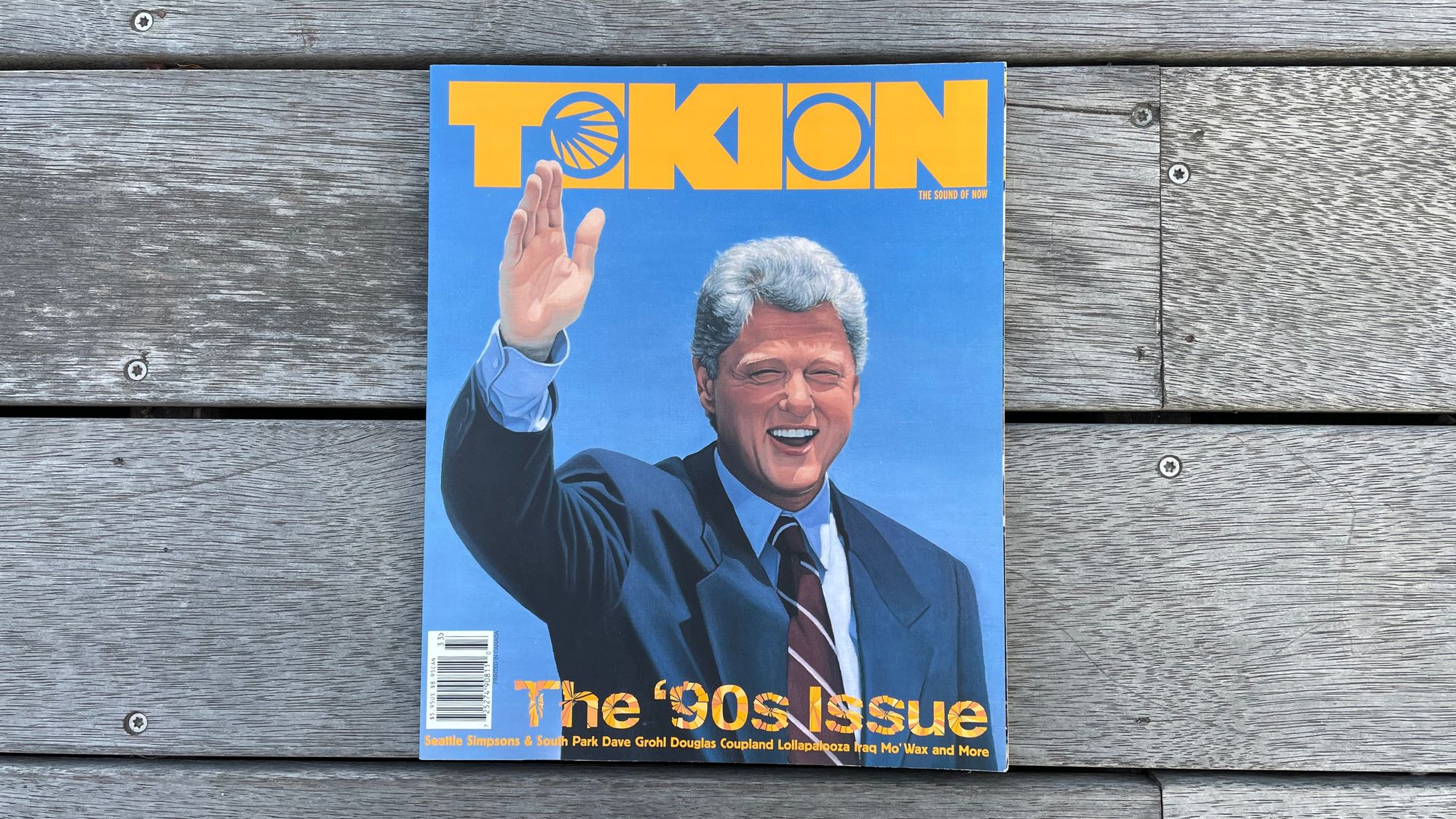

About two months before the world's most terrible people flew planes into the Twin Towers, I joined the staff of Tokion magazine in the Lower East Side. Tokion’s co-founder and American boss, Adam Glickman, had a preternatural talent for always being one step ahead of the indie hive mind (which was itself a few steps ahead of the mainstream). This required choosing left-field issue themes and selecting interview subjects who hadn't made the rounds elsewhere.

Under this editorial direction, Tokion was able to cover things a lot earlier than other magazines, and one of the most insane examples was our hagiographic Nineties retrospective issue — published in January 2003! Yes, barely two years into the new millennium, Adam and team decided it was a perfect time to celebrate the previous decade. We interviewed Sassy’s Jane Pratt, graphic designer David Carson, and The Simpsons’ Sam Simon. I got to phone up MoWax’s James Lavelle. There was an oral history of Second Stage at Lollapalooza involving Lambchop, Flaming Lips, Superchunk, Mercury Rev, Built to Spill, Jesus Lizard, Sebadoh, The Pharcyde, and Yo La Tengo. The cover art was a painting of a smiling Bill Clinton (by Yoko Kawamoto). In both making the issue and looking at it now, there is no question that we loved the Nineties. (And yes, this was 18-months before I Love the '90s.)

I suspect Chuck Klosterman loved the Nineties during the Nineties, but he takes a more detached approach in his new book The Nineties. In the Klosterman retelling, Generation X don't come across as noble heroes. They are hapless, goofy, media-addicted, insular, and deluded. They're ambivalent even about their own ambivalence. Klosterman's impartiality helps the book avoid becoming an OK-Xer nostalgic eulogy. But one thing gets lost in this approach: Part of the story of the Nineties was how much "Nineties kids" loved their era.

In the case of the Tokion Nineties issue, it was mostly meta-commentary on the bummer days of NYC in 2002. Bush won through dubious machinations and installed a hard-right government. (Tokion sold T-shirts with Bush’s face crossed out and the tagline “Not my president.”) And then the aforementioned terrible people flew planes into the World Trade Center. There was great communal harmony in its wake, but also a general dissatisfaction with the cultural moment. As much as the Village Voice hyped electroclash, Fischerspooner’s $1 million album advance seemed like a joke, and then was a joke.

By contrast, the 1990s stood tall as an era of artistic flourishing — a time when smart, edgy indie culture, from Twin Peaks to grunge to Tarantino, earned its rightful place in mainstream media channels. For kids into weird stuff living in the suburbs, these successes rang out like victory bells. Imagine the unbridled joy of hearing Chief Wiggum pull over Homer for speeding and make a Velocity Girl reference on network TV: “Well, well, well, Velocity Boy.” In Klosterman’s framing, “Late twentieth-century adults nonchalantly accepted the possibility that their principal social function was to serve as consumers." Yes, and as consumers of weird things, the 1990s was V-day. MTV used to bury its alternative music clips in a Sunday midnight dead zone; then there was a nightly primetime show called Alternative Nation. The culture cult felt vibrant.

This played out in the status ladder of schoolyards. I went to an all-boys summer camp in North Carolina, and in 1991, pre-Nevermind, the dance with nearby girls camp Rockbrook centered around preppy jock kids hitting on the dolled-up preppy girls. At the Rockbrook dance a year later, post-Nevermind, we moshed to the washing staff’s band's Dinosaur Jr. covers. The popular kids were suddenly the skater guys in long-tees and shorts who chased after the two girls with rainbow dyed hair and black-and-white striped tights.

Klosterman may be right to not nostalgize the Nineties, but it’s worth remembering that many believed it was a golden age, especially in the early Aughts. Compared to 2002, the 1990s felt like a glorious moment of victory and peace.

II. No New Pauly Shores

Had David Halberstam written The Nineties, he surely wouldn't have dedicated a section to the rise of Pauly Shore, but this is Klosterman's superpower. I, for one, had forgotten that an annoying pseudo-surfer MTV VJ became a mainstream comedy film star.

But Pauly Shore is no mere trivia in 2022: His place in the historical record reveals what has changed in the last two decades. There are many irritating weasel-like influencers on TikTok and YouTube — which serve the same role as MTV did. Why have none of those influencers been cast in movies that make millions at the box office?

We can blame the film industry, the influencers for not being traditional entertainers, or perhaps younger Americans' disinterest in film. But without Encino Man-like “crossovers” to more established art forms, TikTok feels much less influential than MTV on the entire cultural ecosystem. Youth culture is fecund right now but somewhat stuck in the cradle.

III. A Chronicle without The Chronic

When someone says “the Nineties,” I admittedly think of grunge and flannel. Klosterman also starts his book there. The debut of “Smells Like Teen Spirit” is the easiest way to pinpoint the Big Vibe Shift. Upon the video's arrival, "the hedonistic, euphoric, high gloss 1980s are over. It took five minutes to killdoze an entire decade."

Most would agree that Nirvana was the defining musical act of the 1990s, but what exactly does that entail? Klosterman also notes, "Garth Brooks was, by a broad margin, the biggest musical act.” Likewise, “For every album sold by Courtney Love, Shania Twain sold fourteen.”

Here we have the essential problem with cultural histories, or really, all analysis of culture: How do we decide on the main protagonist for an era? What represents "the culture"?

The most elementary approach would be to measure sheer popularity. On such a count Garth Brooks wins. But this narrative isn't interesting to cultural historians, who inevitably seek to explain the progression of stylistic change (and tend to write about their own refined tastes). Brooks represented no musical innovation. He sold many records by skillfully reproducing established artistic conventions. As Klosterman notes, "There was no tension between the art he wanted to provide and the art his audience expected."

Nirvana, on the other hand, represented a stark disruption to the reigning musical conventions. Once Nevermind came out, synthesizers and hair metal were passé. Guns N’ Roses' “November Rain” became a relic overnight.

And yet: "Nevermind transformed the totality of American pop culture, and that transformation initiated rock's recession from the center of society.” Nirvana, in its triumph, became rock's last hurrah. Klosterman never explains why this happened, but I'd argue that the minimalist innovations of Nirvana were so easy to imitate that the next 15 years of mainstream musicians, from Alanis Morissette to Bush to Puddle of Mudd to Kelly Clarkson, quickly spun Cobain's conventions into Top 40 pop. The edgy timbres and chord progressions of The Pixies became trite. Indie and experimental musicians looking for innovation had to flee to lo-fi, post-rock, sample-pop, and electronic.

This inevitable pathway from popularity to exhaustion opens up another chore for cultural histories: to write up the origin stories of the sounds that did become influential in subsequent years. From 2022, the most important album of the 1990s is arguably Dr. Dre’s The Chronic, which sold 5.7 million copies and established hip-hop as a true mainstream art form. (Klosterman literally forgot about Dre.) And to explain trap, we'd also need to give more attention to Southern rap groups like UGK.

The narrative overemphasis of acts with later importance is a standard practice in cultural history. We have already shifted the story of the Seventies to explain subsequent innovations: the focus is on The Stooges, punk, and post-punk, not Tony Orlando. The best music book about the 1970s may be Simon Reynolds’ Rip It Up and Start Again about semi-underground artists. David Weigel’s prog rock history The Show That Never Ends finds its narrative hook in the fact that everyone has forgotten how much prog dominated the 1970s.

Klosterman, to his credit, does understand this particular problem. In a footnote, he concedes that he should have paid as much attention to Tupac as Cobain. But for people who lived through the Nineties, it's hard to escape the contemporary narrative; there is easy significance in how much significance we felt in Nirvana and Pearl Jam at the time. And yet I can easily imagine future generations looking back and writing up “Nuthin' but a ‘G’ Thang” as the true epicenter of the youthquake.

IV. Artifacts Slipping Out of the Canon

The Spin Doctors, Ned's Atomic Dustbin, the first wave of emo, OK Soda, Clearly Canadian, Hypercolor, wide jeans, 311, The Adventures of Pete and Pete.