Culture is an Ecosystem: A Manifesto Towards a New Cultural Criticism (2)

A healthy cultural ecosystem provides the maximum number of artistic works that are useful and stimulating to the widest range of people. In the second part of this three-part series, we look at how aesthetic experiences arise from the introduction of novel and complex stimuli, and how a diverse ecosystem organically provides everyone what they need.

2.1 A cultural ecosystem is "healthy" when it produces a wide range of valuable cultural artifacts (artworks, goods, styles) that (1) support social communication and identity formation for all its members, and (2) enable meaningful aesthetic experiences for as many people as possible.

2.2 Culture as social communication: Given that the atomic unit of culture is a convention — a mutually shared expectation among individuals in a community — culture is required for achieving group solidarity.

2.2.1 Sharing tastes forges social bonds between people (i.e. bridges), while discrepancies in taste create barriers between people (i.e. fences).

2.2.2 A contemporary society with a wide variety of sub-units requires a wide variety of cultural practices to sustain the creation of unique identities corresponding to those groups.

2.2.3 Monoculture describes a cultural ecosystem with an inadequate number of artifacts and artworks that satisfy the needs for social communication and identity formation. In a monoculture, people feel unable to express their unique identities.

2.2.4 CAVEAT: An infiniculture with too much hyper-individualized cultural diversity can also reduce social communication. Conventions only find meaning when they represent mutual expectations among many people. No individual speaks their own language.

2.3 Culture's positive effects on the brain: Aesthetic experiences enhance the quality of human life through (1) providing a cure for boredom, (2) broadening an individual's ability to perceive the world, and (3) preparing the individual to deal with future contingencies.

2.3.1 Conventions form our perceptual framework for understanding the world. By challenging conventions, art proposes new ways to perceive the world even through the same external stimuli (e.g. someone who has learned about absurdity as a literary device is able to find humor in annoyance in their own daily lives).

2.3.2 Individuals who have repeated aesthetic experiences understand more conventions, gain greater awareness of their own unconscious biases in perception, and come to value more forms of culture.

2.3.3 Aesthetically sophisticate individuals are likely to become cosmopolitan — i.e. they understand their culture of origin as arbitrary and become open-minded towards alternatives. Individuals with fewer aesthetic experiences are likely to remain provincial: They believe that only their culture of origin is correct, which closes their minds to other conventions and perspectives, and as a result, limits their ability for more aesthetic experiences.

2.3.4 A healthy cultural ecosystem provides a wide variety of aesthetic experiences to the entire population, which in a virtuous cycle, expands individuals' capacity for greater cultural comprehension and preparedness for social change. As philosopher Nelson Goodman writes about the value of art: the "exercise of the symbolizing faculties beyond immediate need has the more remote practical purpose of developing our abilities and techniques to cope with future contingencies.”

2.3.5 Even the most healthy ecosystems contain provincial individuals who reject cultural diversity, yet these individuals still require aesthetic experiences to escape boredom and build community bonds with others.

2.4 The work of psychologist Daniel Berlyne demonstrates that aesthetic experiences arise from the introduction of novel, complex, or ambiguous stimuli.

2.4.1 Humans perceive the world through external stimulus — i.e. sights, sounds, smells, etc. There are some inherent properties of stimuli that have a universal effect on humans (e.g. anxiety from an ambulance siren, slight automated responses from cool versus warm colors), Berlyne, however, concludes that the most important effect from any stimulus derives from what he calls collative variables: how a stimulus compares to past stimuli.

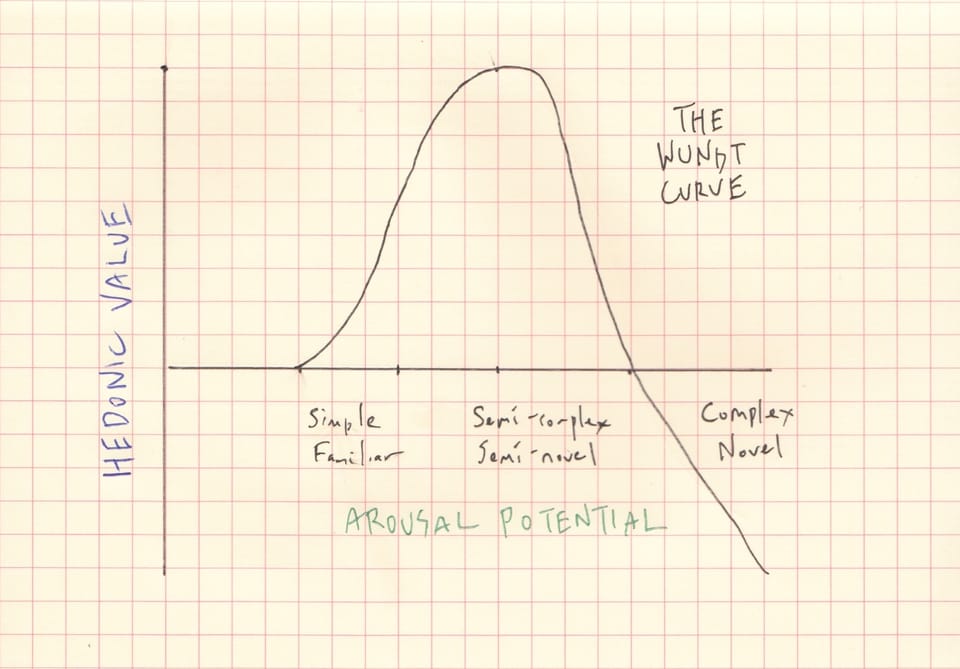

2.4.2 Stimuli can be novel (different compared to the past), complex (time-consuming to decode), or ambiguous (uncertain in decoding) — which are all measured against the individuals' pre-existing knowledge of the world. These variables make up the X-axis of the "Wundt curve" (see graph at top).

2.4.3 Berlyne calls the pleasure taken from aesthetic stimulus "hedonic value," and this can be positive, neutral, or negative. These make up the Y-axis of the "Wundt curve" (see graph at top).

2.4.4 The Wundt curve shows that overly simple and predictable stimuli provide only neutral hedonic value. Positive hedonic value requires stimuli that are somewhat novel/complex/ambiguous. Too much novelty or complexity, however, leads to negative hedonic value. There is, then, a “sweet spot” for the right amount of stimulus novelty/complexity: slightly novel/complex but not too much.

2.5 Since hedonic value is based on past experiences, individuals’ exposure to art in the past changes what they find pleasurable in the present (which is why there can't be universal aesthetics.)

2.5.1 Less experienced and less educated individuals receive hedonic value from stimuli that are not particularly novel, complex, nor ambiguous at an ecosystem level. And for them, overly novel, complex, or ambiguous stimuli lead to negative experiences. This is why most “mainstream” audiences prefer conventional art forms, yet they need some relative novelty or complexity.

2.5.2 Experienced and educated individuals require relatively novel, complex, and ambiguous stimuli in order to have positive aesthetic experiences. Their cosmopolitan meta-understanding of cultural diversity and complexity also means they're more willing to confront stimuli that initially seem too complex or ambiguous.

2.5.3 In needing to maximize hedonic value for as many people as possible, a healthy cultural ecosystem must produce artworks of both relatively simple and complex stimuli. Complex stimuli preferred by experienced and educated individuals are alienating to less experienced and educated individuals, and simple stimuli are not entertaining to more experienced and educated individuals.

2.6 The cultural diversity required to represent social diversity inherently produces novelty, small-scale cultural sub-units tend to produce complexity, and true artists inherently work towards novel, complexity, and ambiguity.

2.6.1 Complex cultural ecosystems with many sub-units provide inherent sources of novelty for the mainstream — e.g. minority cultures, subcultures, and countercultures create new conventions with potential to provide stimulation to mainstream individuals.

2.6.2 Isolated subcultures and countercultures tend to form complicated conventions (echoing the phenomenon that languages spoken by isolated tribes tend to have more complicated grammar and sounds).

2.6.3 True artists produce works that are novel, complex, and ambiguous.

2.6.4 Novel, complex, and ambiguous artworks can always be simplified to make conventional art forms more stimulating for mainstream audiences.

2.7 The commercial marketplace promotes the production of slightly novel artworks by providing financial incentives for creators who can attract the largest audiences.

2.7.1 Creators of slightly novel, complex, or ambiguous artworks tend to receive the most financial rewards because of their likelihood of market success.

2.7.2 Inversely, artists working to create highly novel, complex, or ambiguous artworks are unlikely to find stable monetary rewards — at least, in the short run. They require alternative incentives such as high levels of esteem to create these works.

2.7.3 In their search for novelties, most mainstream-oriented creators import new conventions from the broader ecosystem that feel novel to mainstream audiences — i.e. cultural arbitrage. In merging the innovations with existing conventions, this leads to simplification.

2.8 A diverse cultural ecosystem with both strong non-mainstream units and a cultural industry guarantees some level of cultural refresh — as long as people in the mainstream decide to adopt the innovations.

2.8.1 Mainstream individuals will only accept innovations where they believe there is cultural value — i.e. it sounds/looks "cool," etc. This is easier where the mainstream feels some aspiration towards the originators of those innovations.

2.8.2 Over time the introduction of novel and complex works into mass culture stretches the capacity of mainstream audiences to appreciate more aesthetic experiences (see Steven Johnson’s Everything Bad is Good for You) — e.g. modern mainstream TV audiences can follow more complex storylines than mainstream audiences in the past.

2.9 An unhealthy cultural ecosystem that prioritizes the creation of mass culture and provides no incentives for artistic innovation (1) fails to satisfy sophisticated audiences with enough novelty, complexity, and ambiguity, (2) cuts off the supply of novelties required for stimulating the mainstream, and (3) fails to imbue the population over time with more capacity to enjoy a wider variety of aesthetic experiences.

NEXT IN PART THREE: How critics provide a crucial incentive for novel and complex artistic creation, and how poptimism distorted our understanding of art and culture.